Barbecue. What exactly is it? An outdoor social gathering? The act of cooking outside over a grill? Or is it the grill itself? In the Lowcountry, it’s none of the above. There is only one definition of barbecue here, and it is delicious!

But just how did barbecue become the signature dish of the region?

Some food historians suggest Spanish explorers encountered their first taste of it when they landed in the New World five centuries ago. The native peoples in both the Caribbean and southeastern North America cooked meat very slowly over burning embers in an open pit. The Spanish dubbed this new style of cooking “barbacoa.” However, there is another theory that the French term “barbe-a-queue” — meaning beard-to-tail — that may have been the origin of the word, since the entire pig, head to tail, is cooked. We may never know for sure which language should be credited.

But we do know that barbecue is traditionally pork rather than beef since, in the South, pig farming — rather than raising cattle — was the norm. Pigs were less expensive to maintain since they don’t require large open fields, and they could even be set loose in forests to feed themselves when money was tight. The low-and-slow nature of cooking the meat allows the fatty pork to tenderize and be pulled easily from the bone. Subsequently, pork became a staple in the diet of Southerners.

By the late 1800s, “barbecue men” became famous in local communities for their expertise as pit masters. They were often sought out for annual public holiday celebrations, church picnics and private events. By the 1920s, one such celebrity in Columbia sold his specialty to the public on a more regular basis at his barbecue stand. At a cost of 60 cents per pound, each buyer was required to bring his own bucket.

Barbecue became particularly important in African American culture and cuisine, especially after the Civil War. Emancipation Day was celebrated annually for many years with large social gatherings and the requisite open-pit barbecued pig. When blacks began moving to northern cities in the early 20th century, they took this cooking technique with them, leading many to establish “barbecue joints” there. Cornbread and fried okra became the usual side dishes at those restaurants, introducing urban communities to these traditionally rural Southern foods.

Today, barbecue is often served on a bun, but, before these came into widespread use, two slices of bread were often served on the side of the plate, leaving it up to each individual eater to determine what to do with them.

Pork hash originated in leaner times when cooking every edible part of the pig was a given. Hash is a mixture of a hog’s organ meats and often includes the head, ears and tongue. Simmering these parts in a large pot of water over an open fire slowly for many hours, the contents eventually thicken into a gravy that is served over rice as a side dish rather than as a meal itself. The dish is thought to have its roots in the region bisected by the Savannah River. But Virginians lay claim to originating this recipe as Brunswick stew, a similar concoction that may have migrated southward through the Carolinas and became known here as hash.

So, does beef qualify as barbecue? The idea of using beef rather than pork was conceived later in Texas, where cattle ranches are more prevalent than the pig farms of the Southeast. And, in more recent times, other meats have been now been added to the list of barbecue choices — anything from mutton to chicken to turkey and even fish. But in the barbecue belt — generally listed as Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, the Carolinas, Kentucky and Tennessee — pork still reigns supreme.

With the introduction of electric or gas cookers and charcoal smokers, does it still have to be cooked in an open pit to be considered barbecue? These days, most restaurants don’t have the space or time for someone to labor near a pit for as many as 18 hours to complete the cooking process. Add to that certain health codes in the industry, as well as the potential for fire when

the grease drips from the cooking meat onto the burning embers. So, using modern cooking methods have become common in many establishments. Of course, digging a pit in the backyard and embracing the old-school way is often still done at social gatherings and community events where the guests can enjoy a traditional pig-pickin’.

Adding to the many controversies surrounding barbecue, Southerners will often argue about which type of sauce is the best. And which is the original, and what spawned the various types anyway? There is no way to resolve the first dilemma, since it’s generally a matter of where a person is from and which style of sauce is prevalent there. As to the original, some say it’s likely the vinegar based sauce that is most common in North Carolina and Virginia. The early populations there were British, and they introduced their technique of using vinegar to baste meat as it cooked. Similarly, French and German settlers brought their love of mustard (think Dijon or horseradish) to South Carolina, and the tangy yellow variety became a popular alternative here. The Memphis area’s sweet tomato-based sauce may have stemmed from the availability of a variety of products, including molasses, traveling up and down the Mississippi River. Eventually, this sweet style migrated to Kansas City and blended with peppery and spicy flavors, morphing into the KC-style sauce.

Adding to the many controversies surrounding barbecue, Southerners will often argue about which type of sauce is the best. And which is the original, and what spawned the various types anyway? There is no way to resolve the first dilemma, since it’s generally a matter of where a person is from and which style of sauce is prevalent there. As to the original, some say it’s likely the vinegar based sauce that is most common in North Carolina and Virginia. The early populations there were British, and they introduced their technique of using vinegar to baste meat as it cooked. Similarly, French and German settlers brought their love of mustard (think Dijon or horseradish) to South Carolina, and the tangy yellow variety became a popular alternative here. The Memphis area’s sweet tomato-based sauce may have stemmed from the availability of a variety of products, including molasses, traveling up and down the Mississippi River. Eventually, this sweet style migrated to Kansas City and blended with peppery and spicy flavors, morphing into the KC-style sauce.

So whether it’s beef or pork, pit-cooked or oven-smoked, lathered in sweet, spicy, red or yellow sauce (or maybe none at all), barbecue fans are able to get their favorites anywhere in the country these days, including Charleston, where popular barbecue joints like Home Team, Lewis, Rodney Scott’s and Melvin’s rule the roost. How to properly do barbecue — like politics and religion — is something people may never agree on. But one thing’s for sure: It has become an all-American classic.

HOW DO YOU DO YOUR ‘CUE?

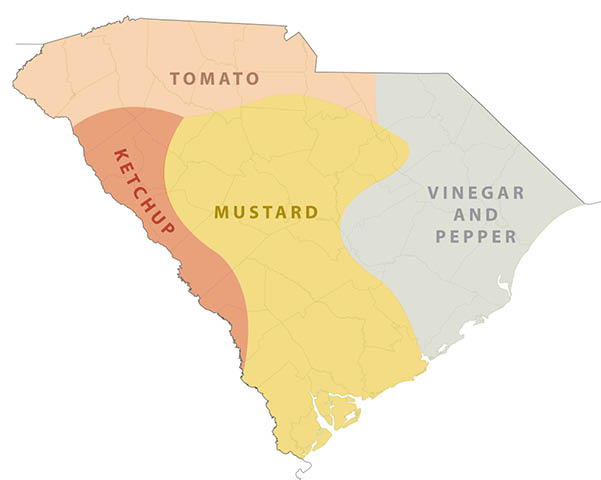

In a sense, South Carolina is a microcosm of the various regions of the barbecue belt. There are four distinct styles: A clear vinegar and pepper blend is dominant in the Pee Dee and along the Grand Strand, likely reflecting the migration from its birthplace in North Carolina and Virginia. The Upstate enjoys a heavy red variety — the kind most often sold bottled in supermarkets. From the Midlands down to the central coast, the traditional choice has been the yellow mustard-based sauce, and the counties along the Savannah River enjoy a ketchup-flavored version. Although you can sample all of them at local restaurants these days, take a journey of discovery and explore the state’s barbecue regions by downloading a barbecue trail map at discoversouthcarolina.com/ barbecue.

Written by Mary Coy