Sometime after my grandmother moved here, speaking and cooking mostly in French, she was given a copy of the cookbook “The Carolina Housewife” – an olive branch from a friend who jokingly thought she might glean from it some elements of cooking in the South. She later handed it down it to me. Written anonymously by “a Lady of Charleston” in 1847 – at that time, the names of Charleston women were traditionally published only at birth, marriage and death – the author is known to be Sarah Rutledge, daughter and niece of two signers of the Declaration of Independence. Her book is a compilation of almost 550 Charleston-centric recipes handed down from her family, friends and acquaintances nearly 175 years ago – for charitable purposes.

The recipes are written, as explained in Rutledge’s preface, “to make it easy to teach the cook to send up the simplest meal properly dressed, and good of its kind … and with no more elaborate abattrie de cuisine than that belonging to families of moderate income.”

Though uncommon in that era, the community cookbook trend ticked slowly upward, coming to a boil in the 1930s, exploding in the 1950s and going strong into the 1990s.

Though uncommon in that era, the community cookbook trend ticked slowly upward, coming to a boil in the 1930s, exploding in the 1950s and going strong into the 1990s.

Charitable community cookbooks have a way of bringing people together by solidifying a sense of community, sharing cherished family recipes, cataloging a unique history of popular local cuisine and cooking trends and providing home cooks a barrage of reliable recipes to make for nightly dinners and special occasions. Combined with the feel-good factor of raising money for a good cause, everyone is a winner.

It’s hard to imagine how many lives have been changed or saved because of a comparatively simple thing like selling cookbooks, but the power of community is strong, and, when multiplied by the many churches, businesses and community groups who believe in their causes, the results are exponential.

Three generations cook with “Charleston Receipts” : Vereen Coen, center, and her mother and daughter.

Chances are, if you are of an older generation and haven’t decluttered in a while, you have shelves upon shelves of these cookbooks – from church, work, the hospital volunteer group, your children’s schools, clubs, country clubs, volunteer organizations and more. Even in researching for this article, as I thumbed through the pages of some obscure copies, I saw familiar last names from generations past. Some quick texts, and come to find out, some of these recipes were from the “great” generation of friends’ families. Some descendants had never heard of the recipes – likely because dishes like congealed tuna salad mold have lost their appeal – and others recalled the family recipes with fondness, not realizing their great-aunt’s famous chicken tetrazzini recipe was still in existence. In a way, the cookbooks planted roots of their own, connecting us to pieces and people of the past.

Many of these cookbooks were home-produced and offer little background as to the authors or what specific causes they supported, though they sometimes included recipes from well-known names of yore. “Hearty Hell Hole Vittles,” for example, appears to be home-printed, hole-punched and tied together with a piece of red yarn, yet it holds favorite family recipes from the likes of former Gov. and U.S. Sen. Fritz Hollings, former U.S. Rep. Mendel Rivers, former Gov. Robert McNair and former U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond.

Others were put together more professionally – and some have had staying power in the Lowcountry over the decades. “Popular Greek Recipes,” originally published in 1957, remains a favorite today. It was compiled by the St. Irene Ladies Philoptochos Society as a fundraising cookbook for Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Charleston and is included in the Walter S. McIlhenny Hall of Fame, which recognizes community fundraising cookbooks. Only books that have sold over 100,000 copies are eligible.

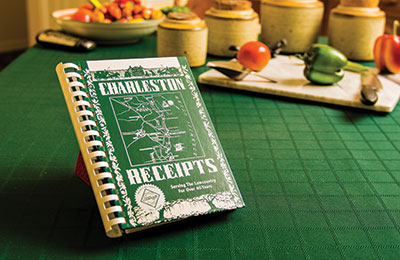

“Charleston Receipts” has remained, resoundingly, the most popular of local community cookbooks. I have four copies myself – three tattered and torn from decades of use and then handed down to me and one more recent copy given to me as a wedding gift. A well-worn cookbook is a well-loved cookbook, and my three older copies are a testament to the reliability of these recipes.

I had the pleasure to sit down with Vereen Coen in her family home where, as a teenager, she helped her mother and a small group of Junior League of Charleston sustaining members compile and test hundreds of recipes. They were solicited from many prominent Charleston families for “Charleston Receipts” in 1950. The ladies’ intent was to raise enough money to hire a speech therapist; there were none in the state.

Now 85, Coen recalled that time fondly: “I remember their excitement – they were just determined to sell it. It never occurred to them that it would be a big success – they believed in their cause, they believed in the cookbook, they loved who they did it with and they loved Charleston,” she beamed. “It was after the war, and they knew people in every city, and they contacted everyone, everywhere, to buy it. They took it in their cars to motels, which were popular at the time, selling case after case to motel restaurants, and travelers would buy them and bring them to their hometowns and stir up interest there.”

The women’s hard work and belief in the cause avalanched and soon put Charleston cuisine on the map, making headlines in national publications such as Bazaar, the Herald-Tribune, Town & Country, House Beautiful, National Geographic, Life and Vogue.

‘“Charleston Receipts’ turned out to be more fun to read than the average best-seller,” Coen laughed, reading a past headline from one of her many scrapbooks on the subject. Now nearing the 900,000-copies-sold milestone, the money raised has supported not just one speech therapist but a hearing center – the first of its kind in the state – and now continues to fund other community projects through a trust.

Today, the community cookbook explosion has been taken off the heat, and while some – like “Charleston Receipts” and a small handful of others – have withstood the test of time and modern factors such as the internet, technology and even the way we live our daily lives.

“It’s a lot of work collecting recipes from people, compiling them and selling the books,” said David Bradley, owner of Fundcraft Publishing.

In the cookbook printing business since 1950, Bradley said 16 printing companies in the United States once specialized in fundraising cookbooks, but today only two remain. He credits his company’s embracing the internet as a reason Fundcraft has withstood the downturn, and they also have branched into other areas of printing. Though his websites offer easy solutions to produce cookbooks – even supplying recipes online that can simply be chosen and assembled – the average community cookbook is becoming a thing of the past.

“People move fast today and don’t have time to look through their recipe books to find something to cook for dinner. They’re looking at recipes on the internet, and they’re going out to dinner. The way most people live these days has changed, and the demand is just not there anymore. Plus, it’s much less effort for groups to raise funds selling candy bars and magazine subscriptions,” he said.

Despite the decline, newer concepts of supporting good causes and preserving great Southern recipes continue to thrive. For example, at Hopsewee Plantation, South Carolina’s first national historic landmark, owners RaeJean and Frank Beatty created “Hopsewee Cooking,” a cookbook that showcases tried and true Southern recipes – some which she serves in the River Oak Cottage Tea Room, a restaurant open to the public on the grounds of the historic plantation – and some which she makes regularly for herself and Frank. The recipes are, as Sarah Rutledge intended with “The Carolina Housewife,” simple and convenient for the average person to cook at home, and many include Beatty’s variations today’s cook would appreciate, like low-fat substitutes or gluten-free options. The cherry on top is that proceeds from it are put back into maintaining the home, circa 1730, and its surrounding grounds and outbuildings.

While community cookbooks may never regain their heyday, they provide an element of culture you won’t find in history books – a unique insight into what foods people fed their families and what recipes they celebrated with. And the money they raised has helped improve the world around us.

The following recipes are favorites from some of these cookbooks. The cocktail sauce is Vereen Coen’s favorite in “Charleston Receipts,” and Meeting Street Crab Meat was a contribution and treasured recipe from her mother. Gin-Gin’s soup is Beatty’s mother’s cherished family recipe.

THE CAROLINA HOUSEWIFE – Shrimp Pie

Have a large plate of picked shrimps; then take two large slices of bread, cut off the crust and mash the crumbs to a paste, with two glasses of wine and a large spoonful of butter. Add as much pepper, salt, nutmeg and mace as you like; mix the shrimps with the bread, and bake in a dish or shells. The wine may be omitted and the bread grated instead. Oysters or crabs may be substituted for the shrimps.

CHARLESTON RECEIPTS – Cocktail Sauce for Shrimp, Crab or Raw Vegetables

- 1 cup mayonnaise

- 1 teaspoon lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon curry powder

- ½ teaspoon finely minced onion

- ½ teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

- ½ teaspoon red pepper sauce

- ¼ cup chili sauce

- Salt and pepper to taste

Mix well and keep in icebox until ready to serve. Recipe provided by Mrs. Horace L. Jones (Louise Dixon)

CHARLESTON RECEIPTS – Meeting Street Crab Meat

- 1 pound white crab meat

- 4 tablespoons butter

- 4 tablespoons flour

- ½ pint cream

- 4 tablespoons sherry

- ¾ cup sharp grated cheese

Make a cream sauce with the butter, flour and cream. Add salt, pepper and sherry. Remove from fire and add crab meat. Pour the mixture into a buttered casserole or individual baking dishes. Sprinkle with grated cheese and cook in a hot oven until cheese melts. Do not overcook. Serves four. (1½ pounds of shrimp may be substituted for the crab).

Mrs. Thomas A. Huguenin (Mary Vereen)

HOPSEWEE COOKING – Gin-Gin’s Chicken and Wild Rice Soup

Servings: Eight

Servings: Eight

- 2 tablespoons oil

- 1 6-ounce box Uncle Ben’s Long Grain and Wild Rice

- 1 small onion, diced

- 2 small celery ribs, diced

- 2 small carrots, diced

- 1 teaspoon pepper

- 4 medium chicken breasts

- 32 ounces chicken broth

- 2 10½-ounce cans cream of mushroom soup

- 1 cup milk

In a large pot, sweat vegetables in oil. Dice chicken then add and sear on the outside. Season with pepper.

Add chicken broth and bring to a boil, then add rice and seasoning packet. Let simmer for 15 to 20 minutes, until rice is cooked. Add mushroom soup and milk. Reheat without boiling.

Note from RaeJean Beatty: At Hopsewee, instead of using mushroom soup and milk, we cook button mushrooms with the vegetables and make a roux with butter, flour and heavy cream. To make it gluten-free, use one cup uncooked white rice instead of roux to thicken.

By Anne Schuler Toole